Background

True continuous integration and deployment are harder than they seem. At least I think so. Its easy to drift or take shortcuts or not really do what you say you are doing. Like everything else in software, it gets harder as you scale. Does every team need a “DevOps person”? Who coordinates new features between teams? O yeah we have microservices right? No need for coordination…

Somewhere around the 30 engineer mark we knew we needed to make a change. Not all teams had the necessary skill sets, some were better at API management than others. Some applications were more stable. Some were taking short cuts. Here’s how we matured our continuous integration approach while scaling to 100+ engineers working on 40+ microservices using GitLab CI, Docker, Kubernetes, and Helm.

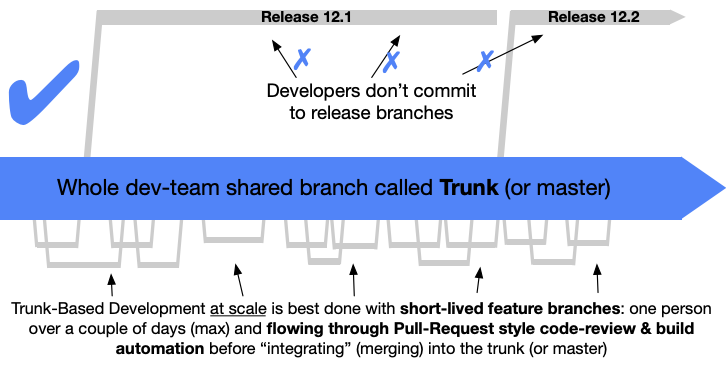

We landed on trunk based development and the creation of a monorepo. The choice to use a monorepo wasn’t made lightly. We decided the benefits were just too great to pass on, even for a small to medium sized group. Statically typed interfaces, atomic commits, uniform large-scale refactors, lockstep dependency upgrades, and shared build tooling have all paid dividends. Similar to the microservice philosophy, a monorepo does come at a complexity and engineering cost.

Some design features of our monorepo:

- It contains everything — Everything needed to deploy every service we maintain. This means source code and Helm charts.

- Single versions — Dependency versions are constrained at the root level via Yarn and Gradle. All projects use the same versions of external dependencies. Internal dependencies always use local references.

- Convention over configuration — We have very specific conventions enabling everything to just work. Add a Dockerfile to your project and the CI job will “automagically” appear.

- Simple workflows — Multi-step incantations must be kept to a minimum. At any given time, a developer can check out

trunkand runhelm install, deploying images built from the exact code they have checked out. Additional overrides can be used to deploy subsets of the system when desired. We work hard to keep deploying as simple as possible.

Building a change

When a developer is ready to commit changes, they open a merge request for their feature branch. Opening a merge request on a feature branch creates a pipeline for merge requests.

Given we are using a monorepo, rebuilding all source images for any given change would be extremely expensive and time consuming. Luckily, GitLab supports detecting which files changed and therefore which Docker images need to be built. Below is an example of a GitLab CI file that will run a common docker-build for foo service.

# Common abstract docker build all builds will extend

.docker-build:

script:

- ./build.sh $SERVICE

# Foo service's docker build

foo docker build:

extends: .docker-build

only:

changes:

- "js/foo/**"

variables:

SERVICE: fooAll Docker builds extend a common .docker-build. In our case, this template calls build.sh. Having a wrapper for things like this is great for codifying conventions or configuration checks. The script will…

- Read

$SERVICEto understand which directory to find the relevantDockerfileit will build. - Determine which type of Docker build we are doing. Are we local on a feature branch? Are we in our CI environment on a feature branch, or just merged into trunk? More on this later…

- Enforce static checks such as linting, unit tests, and image scanning when appropriate.

The nitty gritty

Initially, we created our CI definitions by hand. We found this was error prone and a maintenance nightmare (duh).

To automate this, we wrote a script that will:

- Find all

Dockerfilein the monorepo. - Find the collocated build file — package.json, build.gradle, etc

- Parses the build file for local maven or npm dependency references —

file:../commonLibraryorproject(":commonLibary"). - Output a

.gitlab-ci.ymlcontaining all docker builds.

These were relatively simply to implement. #3 is worth diving into a little bit. We have local libraries that contain common code many services might share. Think client libraries, mixins, statically typed service interfaces, etc. One of the benefits of a monorepo is the ability to reference local dependencies. If a developer is going to introduce a breaking change to their API, they are responsible for updating the client code or working with the appropriate engineers. Netflix has a great post on the topic worth checking out.

-js

|-fooApp

| |-package.json

| |-Dockerfile

|-barApp

| |-package.json

| |-Dockerfile

|-commonLibary

| |-package.jsonAn example directory structure with Dockerfiles and a common library

With all of that automation in place something changes. What I’m describing is something closer to a declarative model for creating CI builds. Rather than every developer updating the CI definition to add their service, they simply add a Dockerfile and run a script (could also be automated). The script handles creating new CI jobs, dynamically resolving local dependencies, and deriving the correct rules and configuration for building. Declarative seems to be a natural progression in the DevOps world.

GitOps: versioned CI/CD on top of declarative infrastructure. Stop scripting and start shipping. https://t.co/SgUlHgNrnY

— Kelsey Hightower (@kelseyhightower) January 17, 2018

Testing the change

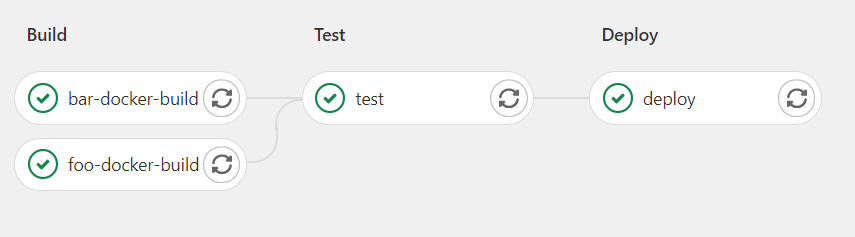

Now that we have feature-branch built, we need to deploy and test it. Our pipeline will need to:

- Allocate a cluster

- Deploy

- Test

I won’t focus too much on allocating the Kubernetes cluster. We keep a pool of test environments but a better approach might be dynamically creating and destroying as need. Maybe we’ll get there one day. One thing to keep in mind is speed. No one wants to wait 3+ hours to get their changes into trunk. We try to keep regression testing to < 30 minutes. In practice, there is a balance between the four DevOps KPIs. How much change failure rate or test maintenance is worth sacrificing for MTTR or time to ship?

Once the pipeline has allocated an environment, it will use Helm to deploy all charts within the monorepo. To do this, our CI pipeline must know which services have new docker images to deploy. Remember build.sh? This script produces an artifact whenever it builds a docker image. The CI deploy job will look for all artifacts and create a set of Helm overrides.

# Install the monorepo charts and wait for all services to be ready

# Override just foo to deploy the new image

helm install --wait --timeout monorepo charts/monorepo --set foo.image.tag=my-feature-branchExample Helm install command for foo image in my-feature-branch

Once deployed, the pipeline can run a suite of automated tests. Just like our services, automated tests are built as a Docker image. This allows us to treat them just like any other service. The only difference is test containers run to completion, so we define the them as a Kubernetes Job.

helm install tests charts/tests

# The job pod should have backoffLimit set to 0 to only run once.

kubectl wait --for=condition=complete job/test

# Once complete, parse the exit code

code="$(kubectl get pod automated-test -o json | jq .status.containerStatuses[].lastState.terminated.exitCode)"

# Pass or fail based on exit code

exit $codeAt this point we should have a high level of confidence the feature branch is ready to be merged. The next thing to do is merge our new feature into trunk. But how does that change become part of the latest deployment?

Integrating the change

For any given checkout of trunk, a developer should be able to run helm install charts/monorepo and have a deployment that matches the code checked out.

Seemed simple enough…we soon realized this presents a real chicken and egg problem.

When a feature branch is merged, we build a new version of each docker image that was updated. We tag the image with a unique id corresponding to the merge request. This gives nice traceability back to which merge request was responsible for triggering the build.

The broken egg occurs when we try to get this tag back to our Helm charts. This tag needs to be checked into source control for helm install to work the way we want. Initially, developers were required to manually update a Helm chart’s values file to reflect the new version.

- Developer opens merge request.

- Developer takes merge request number and updates

values.yaml. - Developer pushes new commit.

But good programmers are lazy. I’m not doing that every time I want to merge something. It also creates lots of merge conflicts.

Automatic versioning

This the dirtiest part of our CI/CD process. When a merge request passes all gates, our CI pipeline makes a Git commit via a bot. This commit updates a special file within a service’s Helm chart named version.yaml.

monorepo/

|-- Charts/

| | foo/

| |-- templates

| |-- values.yaml

| |-- version.yaml # <---- auto-updated

| | bar/

|-- js/

| |-- packages/

| |-- foo/

| |-- bar/Example directory structure for source code and charts

This file is parsed via a Helm named template.

{{- define "image" }}

{{- /* Merge version.yaml with .Values. */}}

{{ - $overrides := .Files.Get "version.yaml" | fromYaml | merge .Values }}

{{ - $tag := overrides.image.tag'

...The beauty of this template is anything in version.yaml can still be overridden by values.yaml or the --set command. The custom file is treated as the lowest priority due to how merge works.

Dealing with conflicts

Constantly churning versioning files means constant merge conflicts. Our first implementation maintained the image tag in the chart’s values.yaml. This was a huge mistake. The problem was this file is used for other configuration items. If the file is only ever used for automated versioning, we can make assumptions about conflicts and therefore automate resolving conflicts.

Conflicts happen when 2 developers update the same service. Two developers, Allie and Bob check out trunk. Allie merges updates to foo which result in a new version. Bob is also updating foo but now has conflicts with Allie’s versioning file. We can be smart about this though. If the versioning file is the only conflict, we can effectively ignore Allie’s update. We can rebase Bob’s changes onto trunk and resolve the versioning conflict with:

# From Bob's feature branch

git rebase origin/trunk

git checkout --theirs charts/$service/version.yaml

# during a rebase, you are now trunk. So take Bob's (their) change.If you want to get real fancy and have access to your Git server, you can actually create a custom merge driver which does this behind the scene. Sadly I cannot. Automatic versioning updates was the final piece to our continuous integration puzzle. Shoutout to GitLab as they use a similar approach for maintaining CHANGELOG files.

Summary

This is the way our team decided to implement continuous integration. It isn’t perfect but it works. Our DevOps journey took us down the road of:

- Creating monorepo specific tooling for maintaining CI definitions.

- Automatic detection of changes for building, testing, and deploying.

- A mechanism for always deploying the latest software.

Continuous integration implementations always feel like a Rube Goldberg machine that functions as a means to an end. Bad automation and workflows make developers less efficient and destroys quality of life. We’ve made those mistakes. But we also learned from them. Hopefully these ideas help someone else struggling to achieve DevOps nirvana… or at least teaches them a couple things not to do. Thanks for reading!